A pile of stained, mildewed debris from Superstorm Sandy has turned into a nostalgic treasure trove for Florida Atlantic University.

A collection of 786 vintage children’s records including “The Little Engine That Could” and “Black Beauty” were inside a Long Island garage when the hurricane-like disaster struck last October. The recordings, mostly 78 rpms, appeared to be ruined due to dirt and mud on the records and stains on their jackets.

But FAU has found a way to bring the stories and music back to life. The Recorded Sound Archives at the Wimberly Library on the university’s Boca Raton campus has embarked on a project to clean and repair the damaged records and digitize and transfer their contents to an online collection. It’s an effort that requires both modern computer software and old-fashioned elbow grease.

“We are excited to be working with such rare and wonderful artifacts from the 20th Century,” said Maxine Schackman, director of the sound archives. “I can’t wait to see the reaction when we are able to share our work online.”

The website likely will be created in November, Schackman said. Researchers, students and others who are interested will be able to access the digital versions of the recordings via FAU computers or a special password, restrictions that are necessary due to copyright.

The collection is full of literary and pop culture classics, including “Bozo Sings,” “Peter Rabbit” and “Mary Poppins.” While most combine stories and songs, some are music only, like “American Folk Songs” and “Alphabet Songs.” There’s a full array of Christmas-themed records as well as plenty of educational ones. A 1947 record called “Little Songs on Big Subjects” includes a gentle call for racial equality.

“You can get good milk from a brown-skinned cow. The color of the skin doesn’t matter nohow,” the song goes.

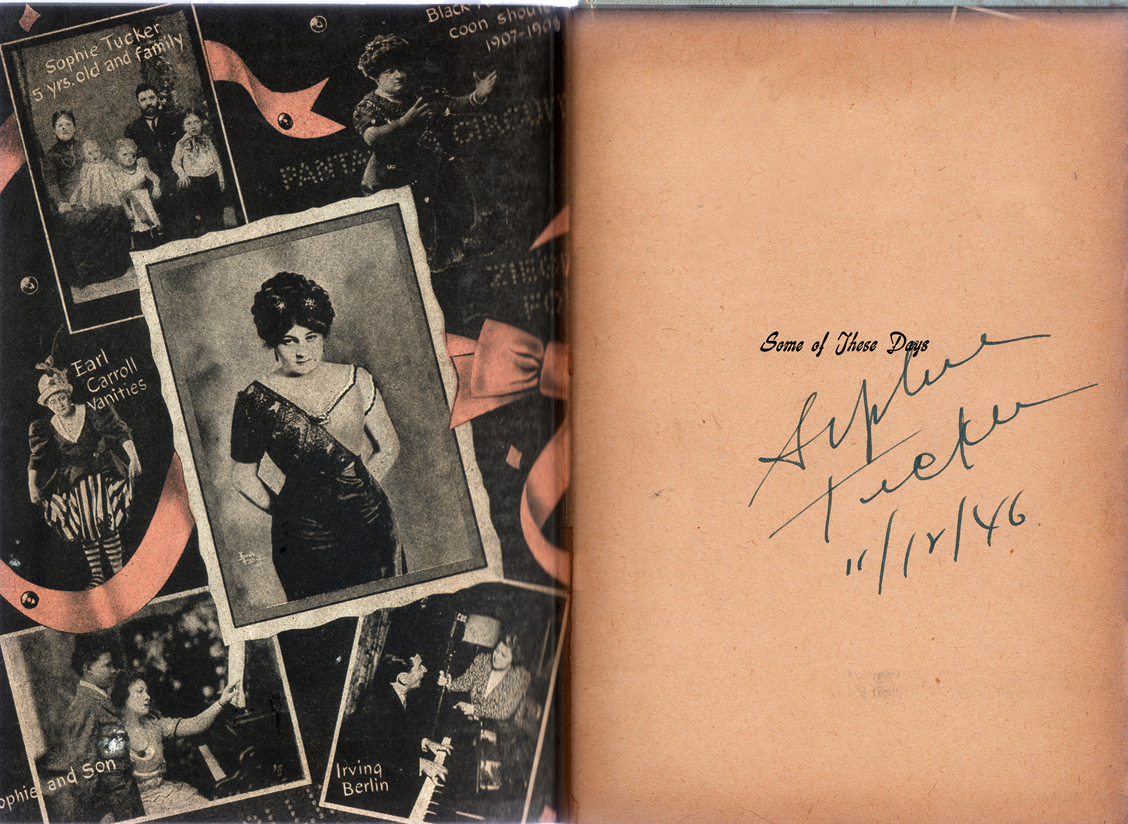

The record collection was donated in April by Peter Muldavin, whom FAU officials call the world’s leading expert on vintage American children’s records. Muldavin, who was out of the country and couldn’t be reached by the Sun Sentinel for comment, says on his website he’s been a lifelong collector but started accumulating kiddie records only in 1991 after seeing one in a used record store and remembering it from his childhood.

He then took out “want to buy” ads in antique newspapers and flea market magazines and was swamped with responses.

“People had these records sitting in their attics and basements but didn’t know what to do with them,” Muldavin writes on his website. “There was no established hobby yet.”

Alethea Perez sorts through some of the nearly 800 vintage kiddie records that were donated to Florida Atlantic University’s Recorded Sound Archives.

Due to mold and mildew damage, the library is discarding many of the story books and paper doll cutouts that accompanied the records affected by Sandy, but photographs of the printed matter are being taken and will be digitally restored using Adobe Photoshop.

Almost all of the records are salvageable, Schackman said. Some are warped, and many are encrusted with mud and must be washed by hand.

To help with the restoration, the archives department has bought a vinyl record flattener, a device that slowly heats the recording between heavy metal plates. The department also has software that can reduce background noise from old vinyls.

The sound archive started in the 1980s as a Judaica Collection of vintage works by Jewish artists, but in 2009 expanded into other genres, including jazz and children’s recordings, after the donation of 60,000 records from the family of the late Jack Saul, a Cleveland collector. That collection included 556 children’s recordings, all in good condition.

Benjamin Roth, a Sound Archivist at Florida Atlantic University’s Recorded Sound Archives, cleans a batch of records from the nearly 800 vintage kiddie records that were donated to the Sound Archives.

Archives technician Ben Roth contacted Muldavin, author of the book “The Complete Guide to Vintage Children’s Records,” last year, months before Sandy formed, for advice on finding some specific titles for FAU’s collection.

When a tidal surge from the superstorm brought 20 inches of sea water into a family garage at Long Beach on Long Island, hundreds of recordings stored there lost practically all their value in the collector’s market. So Muldavin asked FAU if the archives department wanted them.

The Boca Raton-based archivists were thrilled. The collection represents a period in American culture, mostly the 1940s and 1950s, when vinyl replaced the hard shellac material that had been used for records, Schackman said. Vinyl was more kid-friendly since it was less prone to breakage.

The works also represent a period before many families had television sets, and when children’s records were a popular form of entertainment.

“It’s a certain time in history that won’t ever be repeated,” Schackman said. “This was the age of innocence. Times were simpler then, more naive.”

stravis@tribune.com or 561-243-6637

Restoration operation

The process that will be used at Florida Atlantic University’s Recorded Sound Archives on the damaged records:

• A technician cleans the 78 rpm using a special ultrasonic wave machine, similar to the unit used to clean jewelry. Distilled water and a small amount of Jet-Dry rinse agent are used.

• If the dirt is excessive, the record is hand-washed. A hair dryer is used to dry it.

• The record is then digitized, using a special turntable that plays the record and captures the audio onto a computer sound card. Sony Sound Forge software is then used to eliminate clicks, pops and other surface noise.

• The album jacket and any accompanying books or cutouts are photographed. Adobe Photoshop is used to remove any dirt or deformities.

• The audio clip and album art are cataloged.

— Scott Travis

Did you know the Recorded Sound Archives at FAU Libraries has over 49,000 albums along with over 150,000 songs in its databases, which is growing everyday with the help of volunteers? With so many recordings to choose from, we have given Research Station users the ability to request items be digitized.

Did you know the Recorded Sound Archives at FAU Libraries has over 49,000 albums along with over 150,000 songs in its databases, which is growing everyday with the help of volunteers? With so many recordings to choose from, we have given Research Station users the ability to request items be digitized.